Tax on tampons is a hot topic, with Tony Abbott and Joe Hockey in major disagreement. The issue was brought into the spotlight via a petition on communityrun.org.

“And how can a bodily function be taxed? Because the government doesn’t consider the tampons and pads we’re forced to buy every few weeks ‘necessary’ enough to be GST-free.

On the other hand, condoms, lubricants, sunscreen and nicotine patches are all tax-free because they are classed as important health goods. But isn’t the reproductive health and hygiene of 10 million Australians important too?”

I didn’t sign the petition, and here’s why

Sanitary items are different from “condoms, lubricants, sunscreen and nicotine patches”, because people already want to use them, and there is no evidence of significant public health risk if usage falls. Also, “necessity” is not the binding criterion for determining what gets taxed – we tax electricity.

“Half the population menstruates and they shouldn’t be financially penalised for it.

If you still aren’t convinced, let’s consider some statistics: on average women, who make up the majority of people who use sanitary products, earn $262.50 per week less than their male counterparts, and they are also statistically at greater risk of living below the poverty line. Furthermore, this tax disproportionately targets those who may already be disadvantaged, that is the homeless and unemployed.

So why force this underpaid, at risk and disadvantaged portion of society to pay more for basic essentials?”

Healthy women menstruate for about half their life. So, less than 25 per cent of the population menstruates. How big is the financial burden of this tax on them?

A 16 pack of brand-name tampons costs $4 at Coles. Let’s estimate a woman spends $10 a month. GST on that adds up to $12 a year.

The number of people who can’t afford tampons because of GST is therefore negligible. The number of people pushed into poverty because of that $12 slug would be small. Most people campaigning against this tax have no trouble affording $12 a year.

So if you want to make a difference to the financial well-being of poor women, this is an indirect and very marginal approach. It comes with real trade-offs – it would cost the government revenue. That undermines the ability of society to support the poor.

Here’s a petition I’d support instead: raising income support payments to a more reasonable level.

WHAT’S REALLY HAPPENING

If this petition is not really about public health, necessity or fairness what’s it about?

People hate paying tax. They really hate taxes they can’t avoid. They then create ex-post reasons why they should not have to pay tax, generally involving the welfare of the wretched. (Their own benefit is merely incidental to the social good they’re pursuing!).

The mining industry showed the way, with its campaign against the mining tax, focused on the health of small towns and communities. The big polluters mimicked this in killing the carbon tax, worrying about the electricity bills of families on the bread-line.

It’s no surprise these tactics have spread – they’re extremely effective!

The crux here is whether there is a link between fairness and avoidability. Is a tax fair only if there’s a way to avoid it?

Unavoidable taxes are the backbone of our revenue raising system. We already raise lots of revenue effectively through big taxes on things everyone agrees are “good,” like earning income and buying clothes. I’ve previously written that we need more taxes nobody can avoid.

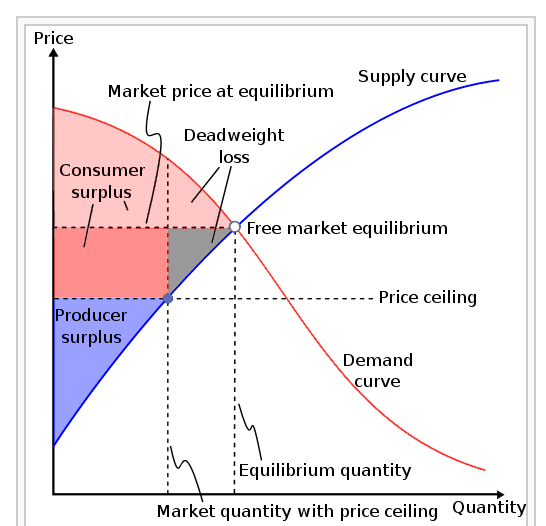

Tax theory says not to introduce loopholes. That was the mantra when I worked at Treasury – maintain the integrity of the system. Always use payments to solve problems, because exemptions are not targeted and get exploited.

But perhaps I am out of step with community sentiment.

Hate for (certain) unavoidable taxes goes back a long way – Poll taxes brought down Margaret Thatcher, for example. Also, exemptions to the GST were what bought it enough legitimacy to be introduced.

I sometimes wonder if sin taxes – tax on alcohol and cigarettes for example – are to blame for the way people see tax in general. A lot of people interpret the tax system as a moral agent judging their actions. If I saw all tax as punishment, I’d be furious about paying tax on sanitary items too.

Tax is not punishment, so maybe we should rename sin taxes to something other than taxes. What we should not do is carve up the system with more exemptions.

Exemptions undermine the efficiency of the tax system but also the sense that tax is our common duty.

I see plenty of normal people arguing that big companies that contort themselves to pay very little tax in Australia are “just doing what anyone would do”. The sense that everyone can and will avoid tax at every turn is pervasive.

I don’t mind paying tax because I can see the benefits it brings. (even though I’m quite aware it’s not all spent efficiently.)

“Tax is what we pay for civilized society.” US Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

—

Thanks for reading this far! If you’d like to agree, disagree or accuse me of obnoxious mansplaining please do so below, and I shall attempt to respond!