The Australian economy is not growing fast enough. Everyone knows it, but we’re in a sort of paralysis, watching the unemployment rate rise.

Consumer price inflation is under control. Normally the RBA would simply cut interest rates, because they’e not impressed with the economy – not one bit. Here’s what the RBA Governor said last week:

“There are sufficient spare labour resources such that we could probably enjoy a couple of years of non-mining sector growth somewhat above its trend rate before we needed to worry too much about serious inflation pressure.”

Basically he’s saying he sees a lot of slack out there, and capital investment is not quite high enough to tighten it up.

So why don’t they act to cut rates? The answer is that house prices are going gangbusters, especially in Sydney,

“Prices have risen in all capitals, with a fair degree of variation: the smallest increase has been in Canberra, at about 6 per cent, and the largest in Sydney, at 28 per cent… a bit more of the ‘animal spirits’ evident in the housing market would be welcome in some other sectors of the economy.”

If they cut interest rates to boost the economy at large, they run the risk of pumping yet more air into the housing market. Because the RBA sets the interest rate but can’t control where investment is made, they are stuck sitting on their hands, hoping something changes. What they really want to see happen is investment (capital spending) in the business sector.

“for accommodative monetary policy to support the economy most effectively overall, it’s helpful if pockets of potential over-exuberance don’t get too carried away.

Turning from housing investment to investment more generally, a more robust picture for capital spending outside mining would be part of a further strengthening of growth over time. Some of the key ingredients for this are in place. To date, there are some promising signs of stronger intentions, but not so much in the way of convincing evidence of actual commitment yet

So while the RBA is in wait and hope mode, we might as well ask why?

Why do Aussies believe buying a flat and holding it for five years will bring us a return, while having grave doubts about the wisdom of opening a panel-beaters, or a cafe, or a farm?

The obvious answer is that we have higher expectations of return from housing than from investing in businesses.

But that is a sort of truism. It doesn’t really give us anything to latch onto and think about. Let’s try to break it down. Here are seven theories of various plausibility on why Aussies might think housing has a better return than investing in business.

1. Pessimism

This topic got quite a bit of air time from a speech just last night by the man seen as the next Governor of the Reserve Bank, Philip Lowe. He talked about the way the community felt uncertain while coming out of the GFC.

“It is important that we guard against the possibility that this uncertainty mutates into chronic pessimism – that is, for it to become normal for us to think that our prospects are limited. If this were to become our normal mindset, then we would be well on the way to finding ourselves in the very world that we feared.”

I’m not too impressed by talking about pessimism, because even if it is 99 per cent of the explanation, it’s not under the control of policy. Better to focus on the 1 per cent you can control.

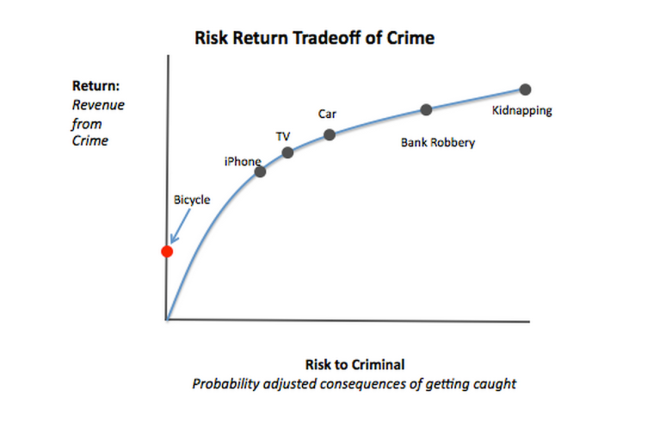

2. Risk perceptions:

It’s easy to turn a million dollars into zero in business. The survival rate is not that great. Of the businesses extant in 2009, 37 per cent were gone by 2013.

Not so in housing. Houses survive very consistently and you’re far more likely to turn $1 million into $1.1 million.

The quick remedy to this is a catastrophic housing collapse. But the good remedy is much harder and more difficult to engineer – better returns to business.

3. Structural change

The flux in the economy recently has many sources, not least the internet, but also globalisation. That makes investing tricky. How to choose the right sector to invest in? Media, finance, manufacturing and retail all look suspect.

If leading businesspeople have experience in sectors that are dying, you can not expect them to invest. It’s hard to expect all that slack to be taken up by the people with experience in organic foodstuffs, professional service or biomedical industries, because they are starting off a much smaller base.

4. Tax structures

Hello negative gearing. Your moment to be led to the chopping block may be nigh.

Given everything that’s happening, do we need more incentives for investment housing, especially for existing properties?

And what about the other side? Do we need lower taxes on business? Could the next CSL, the next BHP or the next Woolworths currently be a medium sized business with a growth plan in the top drawer? What is preventing the owner from making that growth a reality?

6. Pale pink in tooth and claw?

Australia is a country where it is great to be middle class and where Clive Palmer is a dickhead. Why would you even want to be loaded? Alan Bond, Chris Skase, Gina Rinehart, Nathan Tinkler. I’m struggling to come up with a memorable business person that people might see as a hero. Could that be crimping my generation’s desire to risk it all to top the rich list?

6. FDI

Even if Aussies are pessimistic, why isn’t foreign investment picking up the slack? Do they know something about us?

7. The dollar

The Aussie dollar has been ridiculously high. With the mining boom over, it has gone to tumble-town, and hit a four-year low overnight, around US85c. That could be the spark needed to get the economy going again. The RBA must certainly hope so.

Most pages would be the hare-brained schemes of the lone wolves of suburbia. The pages would be underdone and silly. But by asking the community to rate each page, the better ideas would attract contributions from a range of talented people and rise out of the muck.

Most pages would be the hare-brained schemes of the lone wolves of suburbia. The pages would be underdone and silly. But by asking the community to rate each page, the better ideas would attract contributions from a range of talented people and rise out of the muck.