I’ve spent the week scouring the FIFA website, making spreadsheets of the group stages, watching old videos on YouTube, and following Socceroos on Twitter. It’s a clear case of World Cup fever.

Ever since the 2002 edition, I’ve been hooked. I’m not a big follower of local or European soccer, but playing the game on a world stage changes it – not unlike how track and field suddenly becomes fascinating for two weeks every four years, during the Olympics.

I had a formative experience during the World Cup in 2002. I watched Brazil score 6 goals in a couple of early round matches, while other teams looked defensive and dour. That kind of attack was going to be hard to beat, I reckoned, so I popped $10 on them to win at 8-1.

A couple of weeks later I watched Brazil trump Germany in the final and took my winning ticket down to cash it in.

The next two World Cups were especially exciting because Australia was finally involved. I remember being awake and very excited in the early hours of 13 June 2006, when Australia scored three (three!) late goals to win their first world cup match in 20 years.

But expectations are a lot more modest for Australia in the 2014 Cup. Instead of having just one powerhouse of global football in our group, we have two. Spain and the Netherlands. The third group member, Chile, is actually ranked higher than the Netherlands on the FIFA tables. Australia is the lowest ranked team in the cup and Tim Cahill is no longer a sprightly unknown who is given space to score.

Still, World Cup 2014 sparkles with excitement, and that’s mainly because of the Calcutta.

I’d never heard of a Calcutta until last week, but now I am a believer.

It’s a bit like a sweep. You may have been involved in a sweep for a horse race – you put in $2 and get some beast that runs mid-pack the whole way, leaving you with a nagging sense of disappointment.

The Calcutta is designed to compensate for that. Teams are drawn from a hat and participants bid on them. If the team is a dud, there are few bids and it goes cheaply, allowing the possibility of turning a tiny bet into a large fortune.

Our Calcutta was run last night, in the salubrious confines of the Reverence Hotel, in Footscray. (I’d like to insert here, parenthetically, an enthusiastic endorsement of the menu at this establishment and the beef burrito in particular. If gentrification means a walnut and sweet potato salad with your burrito, then I am all for gentrification.)

Before the emerging writers festival crowd took over the back bar with a poetry slam, we auctioned off eight teams and six bundles of teams.

The eight teams were: Brazil, Argentina, Spain, Netherlands, Germany, Portugal, Italy and England.

The six bundles were:

| Asia | Australia, Japan, Korea, Iran |

| Africa | Ivory Coast, Nigeria, Ghana, Cameroon |

| Americas | Mexico, Costa Rica, USA, Honduras |

| South America | colombia, chile, ecuador, uruguay |

| Europe | Greece, France, Switzerland, Bosnia |

| Europe 2 | Russia, Algeria, Belgium, Croatia |

Bidding began in a conservative fashion, when the Asian group was hammered down after only two bids, contributing $2 to the total prize pool.

The prize pool (and whole event) were designed by a local gaming impresario who I shall call Marty, since that’s his real name. 65 per cent to the winner, then 20, 10 and 5 percent for the next three spots.

The interest and excitement of the Calcutta auction process lies in the fact that the value of any team depends not only on its chances of winning, but the size of the prize pool. That’s an unknown. Basically the prize pool depends on how much people are willing to spend. I tried to wheedle this information out of some of my fellow bidders before the game began, but they held their cards close to their chests.

Bidding continued with the Africa and Americas bundles going to me for $3, the only sizeable outlay came when a gentlemen born near Birmingham put his heart into a bidding war and paid $9 for England.

I’d run some analysis in advance that told me bundles were the best way to get value, so I soon set a bidding record for the South America bundle, paying $15.

The feeling of winning an auction is not purely celebratory. What it tells you is nobody else shares your confidence. It can fill you with the fear that you may have just succumbed to the winner’s curse of paying too much.

The thrill of winning a bid was often followed, last night, with a small spell where the winner retreated into themself and stared in quiet contemplation at their ticket. After I bid my $15 (enough to buy 84 per cent of a really amazing burrito) I had my doubts.

But later, as bids rose, my $15 investment in Columbia (rank 5), Chile (rank 13), Ecuador (rank 28) and Uruguay (rank 6) came to seem pretty good. I smiled when Argentina (rank 7) sold for $36.

The auction was fun, involving at one point phone bidding that saw Portugal sold to an outside party. We joked about creating a derivatives market and on-selling our early buys at a profit to anyone who hadn’t been present.

But the big excitement of the evening was the auction of Brazil, host country and favourite. Nobody expected the way the bidding war would turn out for that.

Bidding rose swiftly above the highest price paid. Everyone could see Brazil still offered value, relative to previously auctioned teams and also to the total pot size. But with participants already having invested substantially, and budget constraints starting to loom (did anyone really want to go home and explain they spent $50 on a single bet?), syndicates quickly formed. Two syndicates – one of three persons and one of two – took the bidding up above $50, until finally the Calcutta auction was over with a total prize pool round $200. Markets work, people!

A most satisfactory way to spend a Thursday evening – plus I now have a dozen non-Australian teams to support in the World Cup!

(Back to that derivatives market. If you’d like in on this Calcutta, it’s not too late to buy a team! Make me an offer…)

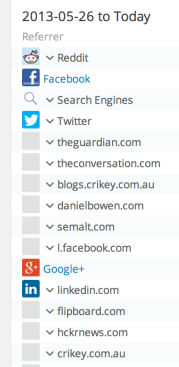

Maybe LinkedIn is not good for the average guy, but if you’re trying to build a brand, it is awesome. Maybe?

Maybe LinkedIn is not good for the average guy, but if you’re trying to build a brand, it is awesome. Maybe?

MattCowgillMay 02, 11:11am via Web

MattCowgillMay 02, 11:11am via Web

The Budget’s unemployment forecasts are higher than the consensus economics forecast (see chart at right). Perhaps because they wouldn’t cut so hard at the moment the economic recovery is gaining momentum.

The Budget’s unemployment forecasts are higher than the consensus economics forecast (see chart at right). Perhaps because they wouldn’t cut so hard at the moment the economic recovery is gaining momentum.