I made this video. Music is by Gomez.

Tag: Melbourne

Melbourne: We should build apartment blocks on our green space.

Melbourne has too much parkland and we should build apartments where there are currently trees.

I am serious. But I am also going to add nuance to that statement…

People who care about cities agree surface carparks are bad. They are dead empty spaces that reduce density. They ruin walkability and limit the agglomeration effects you can get when businesses locate in close proximity.

Many of these same people gush about parks and would chain themselves to trees if I were put in charge.

But there are parks that operate just like carparks. They’re eerie, bleak and deserted. They add to walking distances between destinations. They’re antithetical to the basic function of a city, which is to put humans into contact with each other.

Not all parks are like this. Some are popular destinations in their own right. They are busy and valuable. But others are black holes in the universe of our city.

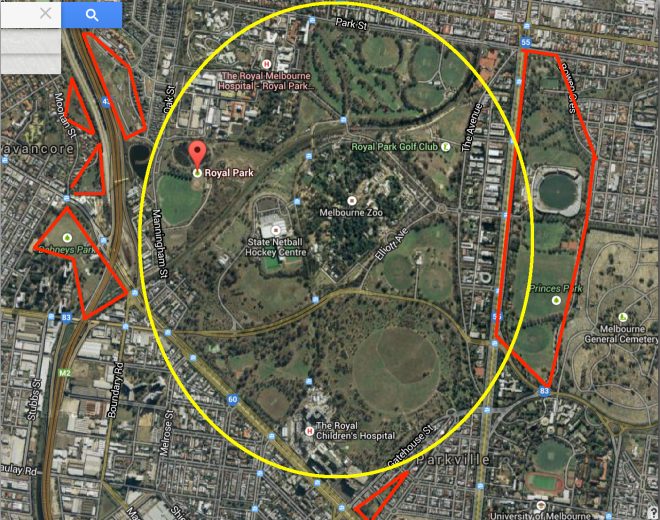

The biggest example of such a bad park sits right at the centre of Melbourne. Royal Park. It is clearly too big and as a result, it is largely empty.

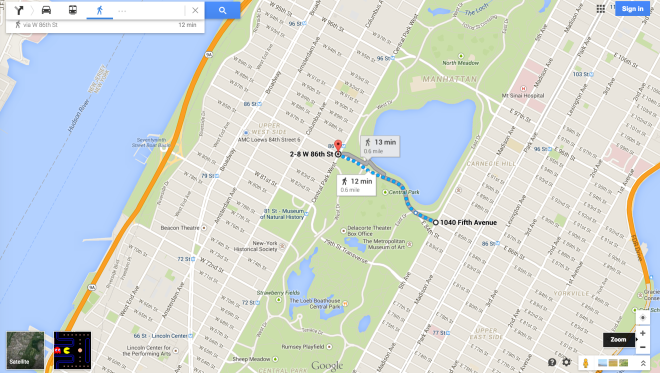

When we compare the scale of Royal Park to another very large, famous inner city park, we can see that it is around 50 per cent wider.

Royal Park and would take 17 minutes to cross on foot. It would take 8.5 minutes just to walk to the middle of the park, assuming you start from the very edge. If you lived 3 minutes from the park and planned to walk into the middle of the park, then home again, that will require at least 23 minutes of solid walking.

While we’re talking about New York City, it is probably worth quoting history’s most famous urbanist, New York’s Jane Jacobs. (Economics readers who haven’t heard of her can think of her as a sort of Adam Smith of urbanism.)

“In orthodox city planning, neighborhood open spaces are venerated in an amazingly uncritical fashion, much as savages venerate magical fetishes. Ask a houser how his planned neighborhood improves on the old city and he will cite, as a self-evident virtue, More Open Space. Ask a zoner about the improvements in progressive codes and he will cite, again as a self-evident virtue, their incentives toward leaving More Open Space. Walk with a planner through a dispirited neighborhood and though it be already scabby with deserted parks and tired landscaping festooned with an old Kleenex, he will envision a future of More Open Space.

“More Open Space for what? For muggings? For bleak vacuums between buildings? Or for ordinary people to use and enjoy? But people do not use city open space just because it is there and because city planners wish they would.”

Parks are an asset to a city. We can appreciate them by looking out on them. We can appreciate them by simply knowing they are there. But mainly we appreciate them by being in them. That’s their primary function.

An empty park is a failed park. These are not like National Parks, designed to preserve an eco-system for eternity. Royal Park is described by its defenders as bushland, but I’ve been to the bush and it isn’t. The modest scattering of trees were probably planted to hide how empty the place is. But it just makes the park more vacant seeming and less useful.

Central city parks should function for people. Design is part of that. Lighting is important. So is seating.

But the most significant determinant of how people use parks is proximity. Central Park has literally millions of people within walking distance. The shape of the park optimises the amount of people nearby – it is long and thin.

By contrast, Royal Park is almost round.

Furthermore, Royal Park is surrounded by other parks! (I’ve marked them in red).

A good park – a necessary park – is surrounded by people who crave access to parkland. Royal Park fails on this criteria.

The only times I’ve ever gone to Royal Park by foot, for reasons other than organised sport, has been in the company of people living in that small, highly-desirable sliver of Parkville on Royal Park’s east. By contrast, I’ve spent many many hours running, barbecuing, football kicking and frisbee throwing in Princes Park, which is basically across the road.

Why would the residents of the dense areas east of Princes Park cross it to visit Royal Park? They wouldn’t and they don’t. That starts a virtuous circle where Princes Park is lively and desirable. Meanwhile Royal Park’s grass grows long and few people notice.

I love parks and I think I have a feeling for what works best. Too small, and they are no fun. I lived in West Melbourne at one stage, and they only have those little pocket parks, built on old vacant blocks. They’re not very desirable to sit in, too small to kick a ball, and not big enough for a dog to run round in.

A good example of a successful park is North Fitzroy’s Edinburgh Gardens. Big enough to have a couple of football ovals in it, and surrounded by medium density housing.

So. With these ideas in hand, how would I fix Royal Park? I present below a fairly modest proposal to split the park along its north-south axis by building high density housing along the tram line.

With these red areas full of homes, Royal Park might finally have a critical mass of potential users. I’ve cut the supply of park only modestly – the vast majority of Royal Park is protected. But by simultaneously increasing the potential demand for this park, it might start attracting a lot more people to appreciate its very real charms.

With these red areas full of homes, Royal Park might finally have a critical mass of potential users. I’ve cut the supply of park only modestly – the vast majority of Royal Park is protected. But by simultaneously increasing the potential demand for this park, it might start attracting a lot more people to appreciate its very real charms.

How to dodge a big payout on cancelling a road contract AND avoid creating sovereign risk

The government of the state where this blog is produced is in a pickle.

Prior to an election last November the then Opposition promised to cancel or defeat in court a contract for a big controversial road tunnel. The tunnel, worth perhaps $6 to $10 billion dollars, has not been built yet. Nothing beyond planning has commenced

Now the former Opposition are in power, they are finding that the old government left them a poison pill.

If the road is not built for any reason, the government must pay the company that would have built it $1.1 billion. This clause was added by the previous government. The companies might have done only $50 million of preparatory work – being generous here – but they get paid $1.1 billion simply for missing out on finishing the job.

Ignoring for a moment the morality of inserting such a clause into a contract (it’s vile, wasteful, ridiculous, and would in a better world result in a range of senior bureaucrats and politicians going to jail), we turn our minds to how the present government can deal with it.

There are three main options.

1. Avoid the payment and make the road. This would involve reneging on a major election promise, but you don’t waste the money.

2. Avoid the road and make the payment. This would gift a billion dollars from an indebted state government to a consortium of companies including Lend Lease Group, worth $9 billion, Acciona, worth €3.6 billion and Bouygues SA, worth €10 billion. It would probably be politically convenient too.

3. Avoid both the road and the payment. The government has one big advantage. It makes laws. It can write legislation that annuls the offending contract. But the big risk in such a course of action is that it establishes an extremely unwelcome precedent that promised payments can be cancelled at whim by the government, and valid questions being raised about sovereign risk.

I want to look more closely at option three. Is there a way a law could be drafted that gets a just result and avoids sovereign risk? I think there might be.

Any law to cancel the payment provisions in the east-west link should:

1. Make it clear that this is a once-off by raising the hurdle for ever cancelling this kind of contract again.

For example, the Government could include a clause requiring that in future passing legislation that annuls any contract above a multi-billion dollar value threshold requires a supermajority in parliament, e.g. two-thirds of votes. The requirement for a super-majority should not apply to contracts where the cancellation provisions are substantially greater than the cost of the work done.

Sovereign risk only applies if a company can genuinely fear its contract provisions may be changed by legislative fiat. If they fear risk, they will raise prices.

Reducing the risk of such legislative action should attenuate the real costs of sovereign risk (although it won’t prevent the political costs of big companies mouthing off about it.)

2. Legislate against any future government ever introducing “poison pill” contract clauses into infrastructure contracts. (Part of me wonders if this law could apply retrospectively?)

3. Legislate that any large contract signed during the “caretaker period” in the lead-up to an election should be agreed upon by the leader of the Opposition as well as the Government, in order to prevent sneaky surprises. Part of the problem with the east-west link project was that it was never an election pledge, was controversial for 3.5 years, and with weeks before the election it looked set to lose, the government signed a contract.

Now. Could the state government of Victoria pass such legislation? It has a lower house majority, so it could pass it there, no problem. In the Upper house it holds just 14 of 40 seats. But The Greens have five, and they are likely to support such a plan. Then the government needs just a couple more, drawn from The Democratic Labour Party, the Sex Party, Shooters and Fishers, and Vote 1 Local Jobs. It might require some side promises, but it may be possible.

I welcome your thoughts and comments on this idea. Please leave a comment below, or hit me up on Twitter.

You won’t believe how much prize money is on offer at the Tennis.

At the Australian Open, first round losers take home enough money to buy three (3) of the automobiles on offer from major sponsors Kia. They can stand on an outside court, not even touch a ball with their racquet, and still take home $34,500.

Even those who fail to qualify for the tournament itself are richly rewarded. 64 men and boys and 48 women and girls have their dreams crushed in the first round of qualifying each year. To compensate them, they get $4000 in prizes. Losing in the second round of qualifying garners you $8000 and losing in the third round nets $16,000. Not bad.

Since I found out the total prize pool at the Australian Open, I’ve been asking people to guess it. Guesses have ranged from $4 million to $12 million. None have come near the true total: $40 million.

The organisers give out prizes left and right. Every player gets something. The Aussie Nick Kygrios takes home $340,000 for making it to the quarterfinals of the men’s singles draw. But he also gets $7400 as his share of a team that lost in the first round of the doubles. (Nick is ranked 1207th in the world for doubles, suggesting that entering the doubles draw might have been about the cash, not his passion for the game.)

The prizes in the singles are greatest.

The most expensive match of the tournament is the final, of course where the loser gets $1.55 million and the winner $3.1 million. But it is also the only round where the winner collects a cheque. In each other round the winner goes on to a chance of bigger and better things. Excluding the final, the most expensive round for organisers, at $2.1 million, is round one, where 64 losers get $34,000.

The prizes are rich enough to cover airfares and accommodation – even for the players who lose at qualifying. Research suggests 150 pros are making enough money to break even in each of the men’s and women’s game. At the same time, some up and comers are probably losing money now in the hope of gaining the experience to make it big later, and others are losing money in the twilights of their career, hanging on in hope of one more glory. (Hi Mr Hewitt!).

So, where is that money coming from?

Tennis Australia’s Annual Report shows it made $193 million last year from “events and operations.” While there’s not much detail, one can imagine that the vast bulk of that is broadcast rights to that highly rare prize, the Australian Open. Channel Seven in Australia pays $20 million a year. The rights globally are doubtless severalfold higher.

Having a grand slam is quite a feat for a country of Australia’s tennis stature. Government supports it, but the support is less direct and therefore less controversial than that provided to the Grand Prix. They prop up the Melbourne and Olympic Park trusts which run the stadiums and have put in hundreds of millions of dollars for their development and re-building. Those stadiums are used for other purposes too, many of which attract tourists from around the world, contributing to the local economy.

Happily, Australia’s tax treaties mean athletes are liable for tax in the country where tournaments take place. So Djokovic, the Williams, et al, all face up to the ATO and hand over a chunk.

Could plans London didn’t use be put to work in Melbourne?

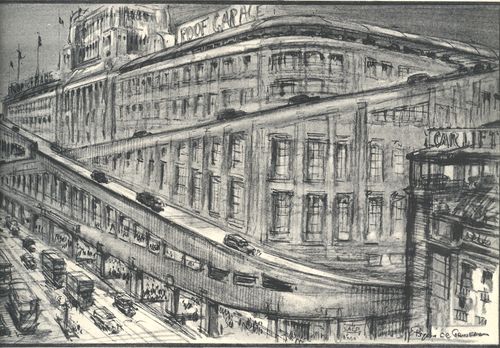

This tweet came up in my feed a couple of days ago, with the accompanying pictures.

Will haunt my dreams. RT @copenhagenize: Nightmarish. Sir Charles Bressey unimplemented London ‘improvements’ (1937). pic.twitter.com/g5x8J0vPg2

— Brent Toderian (@BrentToderian) January 19, 2015

The man who tweeted them, Brent Toderian, is a big name in urbanism, based in Vancouver. Of course he is horrified by the way roads and cars dominate the skylines.

The man who tweeted them, Brent Toderian, is a big name in urbanism, based in Vancouver. Of course he is horrified by the way roads and cars dominate the skylines.

But I saw something in these pictures that redeemed them. I think they are possibly quite smart.

The use of apartment buildings as props for very high freeways was the main aspect that caught my eye. It would not be feasible to drop a road on top of existing buildings. But it may work where you take an existing road, build apartment buildings in its space, and then put the road on top of them.

In talking about this plan, I’m especially thinking of Hoddle Street, which is Melbourne’s Achille’s heel. A north-south road near the city that is choked with traffic almost all the time, it has been the subject of countless studies into how to improve it, with little permanent improvement..

What might work is an idea from left-field, like that illustrated by Sir Charles above.

Here are the upsides I see.

1. Urban infill.

If you take Hoddle Street and fill it with high rises that support a freeway, you get a quick bump in inner city density. Furthermore, the land belongs to the government, so they ought to be able to actually make profit on the property development.

2. Better street level traffic.

The street level near Hoddle Street is a horror story. It’s very unpleasant to walk on because of the traffic – noise, fumes, and on the occasional place where they can build up a bit of speed, the fear you’re going to be killed. The houses along Hoddle Street look cheap and poorly maintained – there is obviously a price discount for being on the road. There is very little retail and not a single cafe or shop with outdoor seating on its whole length.

If the roadway was way up in the air, (and a couple of the many many traffic lanes were retained for a more normal scale street), the street level might be a bit more comfortable for actual use. Cyclists could use Hoddle Street again. Shops might open up.

3. Better amenity because the elevation is so high.

The complaint about elevated roads is the same as the complaint about freeway overpasses. They leave dark empty spaces that are a blight on the urban environment. But if you put the road high enough up in the air, the sense of being closed in will disappear. Even better, if the supports for the freeway are not just concrete pillars but actual apartment buildings, the passive surveillance of these areas would be much better.

I would imagine that top-floor apartments, right under the roadway, would be less attractive as they would get less sun and more rumbles from above. But if they had balconies on the sides the road does not extend, there is no reason they could not be full of light.

The shadow from the entire structure will be vast over a wider area than a smaller freeway, but by having it so high, there will be no single space that is permanently shadowed and unattractive for licit activity.

The obvious downside is the ramping. The illustration shows a six storey building, which would be about 20 metres tall. To descend 20 vertical metres a car needs 120 metres of ramp,( the preferred gradient for public car park ramps is 1:6.)

That would probably have to circle around the building to descend, as per the pictures.. And I’m not convinced the value of the apartments encircled by those exits would be so high. Still, not every building would be an exit, and some exits could ramp away from the buildings.

A more complete set of things being proposed by Sir Charles Bressey 80 years ago can be found here. Nb. I do not agree with turning Trafalgar Square into a multi-storey parking garage.

Myki is set to be replaced. Already.

EDIT: Additional details have been drawn to my attention and it seems the proposal is to add the paypass system to the existing Myki system, rather than wholly replace it. That, to me, seems to add even more complexity and cost and the arguments below still stand.

—

I feel like we’ve just got the hang of Myki.

The smartcard system that came in in 2010, finally replacing the extremely functional metcard system in 2012, had a few bad years. But now I see people touching on and off more or less correctly. There’s a lot less waving of cards near the readers and a lot less theatrical sighing.

Nevertheless the coalition government is suggesting they will turf the system if they win power again. Transport Minister Terry Mulder has said that the government will look into using the Visa Paywave / Mastercard Paypass system at the barriers instead.

I quite like the sound of that. But I’ve learned to be wary of things I like the sound of.

Myki was supposed to be the smartcard to end all smartcards. The reason the government spent nearly $1 billion developing it was that it was supposed to be adaptive. The technology was meant to grow with the city, and give us the option to change our ticket system without changing our smartcard system.

Even the savvy were fooled. Here’s PT guru Daniel Bowen being quoted in 2006:

“It will be a vast improvement over the current system. However, some passengers may find having to scan on and off an inconvenience.”

If only the biggest issue was touching on and off!

The reality has been that the Myki system cannot even do what the previous system could do. It can’t manage short-term tickets, it fails often and it struggles terribly on trams, meaning the mantra “remember to touch on, and touch off” became untrue for (most) tram users.

But the big lesson is not that Myki is bad. It’s that replacing Myki is going to be expensive. More expensive than people imagine. And the solution will almost certainly deliver less functionality than you hope. This is the lesson of big projects. They run over-budget and deliver under scope.

I’m no great fan of Myki. But let’s not repeat our mistakes by turfing Myki out before we’ve wrung the last drop of value out of it. Let’s not repeat our mistakes by assuming the new ticket system will be both easy to use and flexible. And let’s definitely not repeat our mistakes by replacing it with an elaborate bespoke system.

The temptation for a minister will be to cave to special interests, so “Simply Using Paywave” turns into a giant cluster-cuss of exemptions and special rules in special places, requiring a lot of bespoke software that fails a lot.

Lastly, let us always remember where our ticket fees go.

A ticket system is very expensive to operate. A big chunk of the cost of every ticket goes to paying for the tickets, the ticket machines, the software, the inspectors, the public servants that administer the ticket system, the inspector system and the fines – not to mention paying for the judges that hear the complaints in court. Only a fraction of your fare goes to actually making the vehicles run on time. There would be plenty of efficiencies from making public transport free, instead of using tickets.

The real difference between Melbourne and Sydney: Longitude

People think of Sydney being north of Melbourne, but if you went due north from Melbourne until you got to Sydney’s latitude, you’d be 580km due west of the Opera House.

In fact, the east-west distance between Melbourne and Sydney is almost exactly the same as the east-west distance between Melbourne and Adelaide. (Both are just over 6 degrees of longitude difference).

The result of this is different times of daylight. A good friend of mine who works between Sydney and Melbourne says the early sunrises in Sydney get him up and running before work, which he never does in Melbourne. But he misses the languid light of Melbourne’s evenings after leaving the office.

Both sunrise and sunset are later in Melbourne, all year round. This graph shows sunrise, and sunset a for both cities. Melbourne is the yellow and red lines, Sydney the green and purple. The difference is almost an hour.

The difference manifests itself in interesting ways. I reckon Sydney’s surf culture is nourished not just by the warmer weather and better beaches, but also by the fact there’s hours of sunlight before work. The pop-culture phenomenon that is Aquabumps could only thrive in Sydney.

There’s evidence of a much stronger early morning workout culture in Sydney too.

Further evidence: The Milson’s Point pool opens at 5.30am. The Fitzroy pool opens at 6am.

The Sydney-siders seem to be making the most of their early mornings. Are we Melburnians missing out?

What we get is a bit more evening time to spend outdoors. This works well for Melburnians in summer, when, for example, the Sydney Botanic gardens shut at 8pm and the Melbourne Gardens are open til dusk.

Much like daylight savings, being further west in a timezone moves daylight to the after work hours.

The great advantage of having more light in the evening is supposed to be using less power around the home. But because of the different energy mixes between Melbourne and Sydney, (the southern capital uses a lot more gas) and the temperature differences, it’s hard to compare. And with the declining role of lights in electricity use, and the rising role of air conditioning, sending people home from work in the heat of the day may have the opposite effect.

So which is better?

The concept of solar time means you can measure which timezone is closer to “accurate.” This maps shows Melbourne is in the red, with an assymetric sort of day, and Sydney closer to balanced. If Melbourne’s time zone explains my tendency to get up late and stay up late, it has a lot to answer for.

The case for finely balanced time-zones is most obvious where they are absent.

China uses just one time zone, creating giant differences between one end of the country and the other. During daylight savings, the sun sets at 10pm in Lhasa, and two hours earlier in Shanghai.

The vast majority of the world is in the red, suggesting people like the evening hours to be daylight. But if you look closely, a lot of very dynamic cities are in the green parts of the map: Tokyo, New York, LA, Shanghai. Perhaps there’s something to this “early to bed, early to rise” idea.

Should Melbourne perhaps change time zone? If we moved to Adelaide time, we’d see sunrise as early as the Sydney-siders do. Then the only reason not to spring out of bed and do exercise would be the weather!

The Sydney Harbour Bridge was a bad mistake.

There are lessons in Australia’s history we can learn from. One of them is the screw-up that is Sydney.

Sydney was well-placed to become the London of Australia. A prime location, settled first, the early seat of power. It had it all. But while London remains by far the wealthiest and biggest city in the UK, Sydney is on-track to be overtaken by Melbourne in population.

If Melbourne overtakes Sydney, it won’t be the first time. Sydney had a 40-year headstart and yet lost its lead in the 19th century. At that stage the reason was the Gold Rush. Sydney got its lead back when a financial crisis hit in the 1890s.

If Sydney is overtaken by Melbourne in population, you can’t blame the Sydney-siders. They work hard, but they’re behind the eight-ball. The problem is the harbour.

If you think of it as public space, it’s lovely to look at and nice to use. But if you think of it as distance, is it smart to put so much of it right in the middle of your city? Do you really want so much distance between inner-city suburbs? Wouldn’t it be better to have a network of streets?

I contend that the harbour creates a massive problem in the middle of Sydney. The CBD is unable to connect properly into adjacent suburbs because they are a ferry-ride away.

That explains articles like this: “Why is Sydney’s CBD growing slower than Melbourne’s?”

Sydney has more than one major business cluster. The city competes with North Sydney and Parramatta.

But I’d argue that’s a sign of weakness, not of strength. Of course every city has suburban centres, but powerhouses like New York and London aren’t confused about where might be the centre of power, or the best spot to locate a business. Sydney’s situation whispers: this city is too big to really be one functional city. But globally-speaking, Sydney is not even that big, population wise.

So, the harbour in the middle could be part of the problem. But the harbour became the centre of Sydney only when a bridge was built that made the north shore more accessible. You can see the population develop in this video and the north only really takes off after 1932, when the final rivet was painted.

The smart move would have been to densely fill in the area to the south, intensively, before building to the north.

We’ve all played computer games where you have to build certain things in a certain order. If you build too many of the wrong thing too early, you get out of whack, run out of gold and you can’t beat the game. I’d argue that’s what Sydney did.

The Bridge was built using £6.25 million of public money. That represented about 2 per cent of NSW’s GDP at the time. For comparison, 2 per cent of GDP now would be about $10 billion. (sources: 1, 2)

Despite using tolls to pay it off, the debt lingered until 1988.

The opportunity cost? Not just the proper development of contiguous land areas, but also what that money might have bought if spent differently. When the rest of the world was building world class public transport systems, Sydney let theirs go.

There is a common trope that argues the Sydney Harbour Bridge would not have passed any sort of cost-benefit analysis. This is generally used as part of an argument against cost-benefit analysis, with the assumption being that the Sydney Harbour Bridge is good. Of course it has a lot of value now, in tourism terms. But in 1932, when it opened, tourism was a rather minor part of the economy. (It’s worth noting that the Bridge was built against the advice of the government’s infrastructure adviser, which recommended a cheaper tunnel.)

If Sydney didn’t build the bridge, the city might have simply left the harbour as a boundary on the north. Of course some people would have chosen to live there still, but probably fewer. There’s plenty of space to the south that could have become very desirable had the economic centre of the city not been shifted north by the “coat-hanger”.

But building the bridge was not the end of Sydney’s attempts to link north and south. With booming northern suburbs and an incipient northern CBD, it threw good money after bad with years of very expensive ferries and then the construction of a tunnel opened in 1992. The Bridge may soon need to be replaced, due to rust.

But forget the money. I’m arguing that the bridge moved the harbour from the north to the middle of Sydney, and that hurt.

This whole argument rests on the idea – coming back into fashion – that infrastructure is “city-shaping.” That means you oughtn’t merely provide for existing demand, you should understand what you provide will shape future demand.

Bodies of water are city-shaping. They are often part of cities because of the history of water transport, but now hurt urban connectivity. For example, Oakland remains the very poor cousin of San Francisco.

Even rivers seem to have an impact.

London has lots of bridges but the wealth and the productivity is overwhelmingly on one side of the Thames. It required Manhattan house prices to reach many millions before Brooklyn got any buzz, and Shanghai only developed the far side of the Huangpu in the last 20 years.

By this logic, curvy rivers would be especially bad because they divide the city more. In that respect, Tokyo is better off than Brisbane, because the Sumida River flies like an arrow compared to the meandering Brisbane River. (There is evidence that a single bridge built in Brisbane recently has had a big influence on where people live.)

I’d be very interested to see a meta-analysis of whether, in the last 50 years, the value of having a river has turned from positive to negative in terms of a city’s economic growth. The impediments a big river would create to city connectivity are likely to be significant, especially where bridges are in short supply.

All this is very interesting, but we can’t go back and unbuild the Sydney Harbour Bridge. So what’s the point?

The point is we can learn a valuable lesson. Don’t spend valuable taxpayer resources providing infrastructure that will “shape” your city in the wrong way.

Infrastructure is extremely durable. Every mis-spent dollar will spend centuries choking your city. If it accidentally facilitates growth in hard-to-access places, or encourages inefficient kinds of transport use, infrastructure spending can be the enemy of a good city.

RBA calls it: Australia’s housing market has gone horribly wrong.

“Unbalanced” and “out of proportion” are the words they use in a brand new report out today.

“Recent housing price growth seems to have encouraged further investor activity. As a result, the composition of housing and mortgage markets is becoming unbalanced, with new lending to investors being out of proportion to rental housing’s share of the housing stock. “

Do not get the impression the RBA thinks this will be a minor:

“In the first instance, the risks associated with this lending behaviour are likely to be macroeconomic in nature rather than direct risks to the stability of financial institutions.”

nb. “In the first instance…”

Who knows what sort of calamity could follow a macroeconomic event associated with a big house price fall? And if you think not owning a house makes you safe then you are wrong.

“…a broader risk remains that additional speculative demand can amplify the property price cycle and increase the potential for prices to fall later, with associated effects on household wealth and spending. These dynamics can affect households more widely than just those that are currently taking out loans: the households most affected by the declines in wealth need not necessarily be those that contributed to heightened activity”

This chart got the RBA concerned:

“… expectations of future housing prices seem to be influenced by the recent past (Graph 3.4). This tendency was stronger than average in New South Wales and Victoria at the end of last year. The risks associated with this behaviour are likely to be macroeconomic in nature if households were to react to declines in their wealth and any repayment difficulties by cutting back their spending. “

The recent rise in interest-only loans (yellow line below) also has the RBA worried about whether speculation is rife.

They are so worried about house prices they are cracking open the weapons safe and rustling around for some ammo to try to scare off packs of hungry investors.

“The Bank is discussing with APRA, and other members of the Council of Financial Regulators, additional steps that might be taken to reinforce sound lending practices, particularly for lending to investors. “

The most likely step is not to mimic NZ and try to control Loan-to-Value ratios (as you can see in the above graph, LVRs seem to be under control). It is to make banks add a bigger buffer to their lending criteria. Currently they add 2 per cent to the existing interest rate. That might rise.

The last warning the RBA delivers may be important for anyone considering buying a small apartment in central Melbourne:

“A speculative upswing in demand can also be damaging if it brings forth an increase in construction on a scale that leads to a future overhang of supply. This risk is more likely to arise in particular local markets than at the national level.”

CAVEAT: The RBA points out that housing market dynamics are most skewed in Melbourne and Sydney. I’ve noted myself that buying in Brisbane looks like a pretty clever move.

FULL DISCLOSURE: The author is not invested in property.

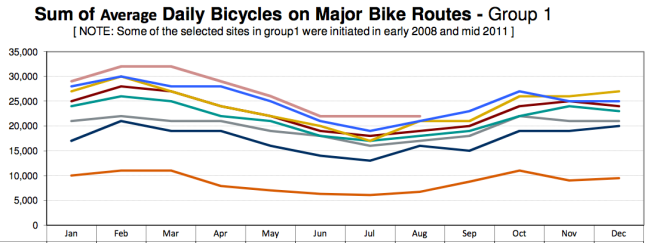

How much should we spend to get cycling up to 5 per cent of trips?

Melbourne’s weather is poor. It rains often. The city is huge – 100 km from edge to edge – and vast swathes of it are covered in the kind of densely packed contour lines that make cyclists legs tremble.

In winter, Melbourne’s cycling community shrinks by over a third.

On days like today I suspect the number of cyclists is far smaller.

In short, Melbourne will never be the sort of city where 50 per cent of trips are possible by bike. Cycling (and walking) will never ever do the “heavy lifting” in our transport mix. That role will always be split between public transport and private motorised transport.

At the moment, the mode share split between these three is:

And the trends are these:

Cycling is growing fast, more than doubling in eight years.:

Public transport growth has been its highest in sixty years, with train travel accounting for most of the increase:

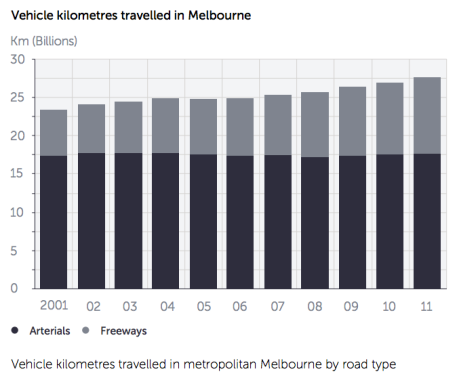

And vehicle kilometres have surged on freeways, while not increasing on arterial roads.

Expenditure on specific infrastructure looks like this:

Nationwide, spending on cycling is $112.8 million. Spending on roads is over 100 times more, at $18 billion.

The data is tough to aggregate, but one estimate is that roads get four times the investment of public transport.

All the modes are growing. How do we decide what the data means? And why not let the market decide what modes live or die?

The answer to the second question is that transport is going to be a centrally planned space until we can charge users per kilometre.

Public roads built to accommodate cars push the whole investment process into the world of “second-best.” If subsidising roads is a given, subsidising public transport can be efficient. Subsidising public transport makes policy makers wonder if there are other, cheaper ways to move people around, like bikes.

So if we’re going to be centrally planning our transport mix, we must ask: do we like the current 78/17/5 mix?

I’d argue we should not. I’d argue we should be aiming to grow the share of modes that have fewer negative externalities and greater returns to scale.

I’d hazard a guess that for Melbourne, 10 per cent share evenly split between walking and bike, 30 per cent for public transport, and 60 per cent for cars would be optimal.

Does that mean we should start spending 10 per cent of infrastructure funding on active modes, 30 per cent on public transport and 60 per cent on cars?

Only if we want to move very very slowly.

Infrastructure lasts a long time. That means the stock of existing infrastructure is the single biggest determinant of infrastructure in five years time. Marginal changes in expenditure rates affect outcomes only very gently. If we want to effect change, we need to tip the scales massively in favour of the modes we want to grow, in the short term.

That means that announcements like $650,000 for changes to a cycling bridge in Melbourne’s west should not be cause for widespread congratulation.

In the short term, we could probably usefully spend 60 per cent of the transport infrastructure budget on public transport and 15 per cent on active modes. If we did that for a few years, we would move swiftly towards the outcomes we want, before returning to a “maintenance” split, where expenditure is based on usage.

Spending even $500 million a year on bicycle infrastructure might seem like a lot when the recent budget has been around $30 million. But when you look at what passes for “bicycle infrastructure” and imagine replacing it with global quality bicycle infrastructure, it would be a drop in the ocean.

I don’t imagine gold-plated bicycle infrastructure should go everywhere. Far from it. Cycling infrastructure should be optimised in the areas where cycling can thrive, likely to be areas that already see some bicycle traffic. Fixing missing links, creating Copenhagen lanes on major on-road routes, plus widening and lighting off-street bicycle paths would be the top three priorities.

If we want to increase the share of some modes, we need to be bold about throwing money at them, and not be afraid to acknowledge that such a move comes at the expense of other modes.

Faster train journeys – some low-hanging fruit.

The state government is prepared to make big investments to make train travel easier and faster. So they should. They are contemplating a $9 billion tunnel that will make journeys faster and more reliable.

But what if I told you there was a much much cheaper way to improve travel times of the rail system, while making people’s journeys to work more comfortable?

The solution requires thinking outside the box. This is not about putting faster motors on the trains. Not about improving signalling or driver training or anything to do with the train system itself. It’s about cutting walking times to the station.

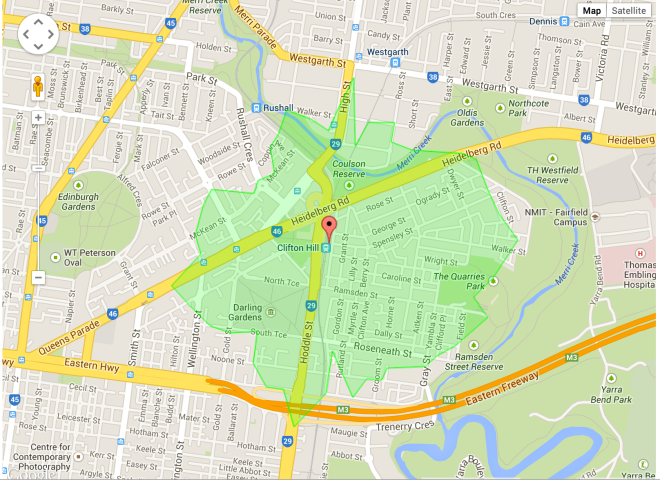

Let’s look at my local station, Clifton Hill.

There are just three entrances, all clustered up the northern end of the station.

This is not a passenger-centric design, but an operator-centric design.

Walking times are some of the most important parts of a train journey. A meta-analysis of the subject cites research that found ten minutes of walking was equivalent to 20 minutes of riding in the vehicle. In other words, the walking section of the journey is an important place to focus improvements.

I’ve made a model for the benefits at Clifton Hill station. Clifton Hill Station got 3,009 boardings per weekday in the 2011-12.

I model it like this: 25 per cent of the users who walk to the station live in line with the platform, so moving entrances to the end is of no benefit, while 75 per cent of users currently walk past the end of the platform to get to the entrance. An amazing isochrone map app I found shows that my model is probably conservative, because of the local geography.

There are 90 car parks at Clifton Hill Station, and it is served by buses. There are trams not so far away. I estimate two-thirds of people walk to the station. (2000 users a day.) Let’s say 1500 of them could potentially access the station via the new gates I propose.

But smart public transport users know not all carriages are equally useful. Depending on what station you get off at, and where you’re headed, your train exit may be speeded up most by being at the front, back, or middle of the train.

If you come to Clifton Hill Station from the south, but you want to board the southbound train’s last carriages (and you’re not running late) it provides you no advantage to have an extra gate at the south end of the station.

But if you’re coming from the south and you want to be in the front carriages of that southbound train, you need to walk that distance twice. Once along the street outside the station, and then back again along the platform.

| Putting an entrance at each end of the platform, replacing a northern-end entrance | ||||

| – | WALKING DISTANCE SAVED (m) | |||

| – | Southerners | Middlers | Northerners | |

| front carriage riders | 150 | 0 | 0 | |

| mid train riders | 75 | 0 | 0 | |

| last carriage riders | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

12 per cent of the 2000 walkers will save a conservatively estimated 150 metres, or 90 seconds. 12 per cent of them will save an estimated 75 metres, or 45 seconds. That adds up to 563 minutes on access to the station. That makes 9.4 hours. If the same effect is present when they return home, it’s worth 18.8 hours.

The model does not assign any benefit to all the trains that may now *just* be caught when before they were just missed.

Assuming a value of time of $30 an hour, the value of the additional exits would be $146,000 a year, just measuring weekday trips. For a gap in the fence, a bit of concrete paving and some extra Myki machines, which I estimate to cost perhaps $500,000, it would pay itself off within a few years, yielding a positive rate of return.

You may think a minute here or there is not important, but there is no single change that can cut a train journey’s duration in half. If we want improvements to service we need the operators to accumulate small easy changes like this across the network.

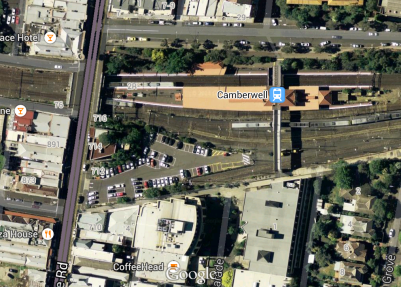

Clifton Hill Station is not even the worst offender. Camberwell station has the entrance to two of its three platforms about 100 metres away from the main road it serves.

Why haven’t they thought of these fixes already?

There will be a perceived trade-off with safety. I don’t doubt the ex-post rationalisers are currently saying “but having one entrance allows for surveillance!” But a single entrance also funnels station users past a single choke point. In the same way a narrow alley feels dangerous at night, so can a single station entrance with no alternatives.

In fact, more exits and entrances should mean fewer people spending time at stations, increasing the visibility of anyone loitering with malicious intent and decreasing their opportunities.

I contend the reason this sort of station design is not widespread is institutional. The Public Transport Victoria guidelines for station design seem to support this kind of solution:

“Many aspects of the local context and surrounding urban design will influence the station entry configuration. A thorough study of the station catchment area is required to determine the most appropriate placement of the entry or entries in order to attract patronage by:

a) Encouraging the use of the station by simplifying connections with existing and future urban design;

b) Providing accessibility, convenience, clarity and quality of arrival to and from the station;

c) Providing safe and attractive public spaces that contribute positively to the local identity;”

But in fact, station access runs second to concerns over train boarding patterns. PTV tries to alternate whether station entrances are at one end of the train or the other, to prevent any one carriage getting too full. Their conception of their job focuses on the trains, not the passengers.

But building more station entrances should be a priority. It won’t help just walkers. At the margin, making walking distances to train stations shorter will encourage more people to walk, and free up scarce car parking spots for people who live even further away.

As well as institutional bias from the departments, there is a ribbon-cutting bias in public transport investment. Politicians want grand visions. The Premier can’t imagine himself showing up to the construction of a new station entrance, so he doesn’t push for it to get done. But that doesn’t mean it’s not the best idea.

The reason US Southern Style BBQ is taking off in Australia has more to do with economics than you think

In Melbourne, you can’t turn a corner without discovering some old Italian bistro or Chinese restaurant has turned into an American Rib joint.

There’s Ribs n Burgers, Le Bon Ton, Third Wave Cafe, Meatmother, and Big Boy BBQ. All of which are new, all of which are packed.

Sticky, delicious ribs aren’t the only State-side innovation taking over the menu.

There’s also Po’Boy Quarter on the Fitzroy side of Smith St, the Gumbo Kitchen food truck and the Sookie La La Diner where you can get waffles with bacon and maple syrup.

The whole city is suddenly buzzing with American cuisine – and just a few short years ago, that would have seemed like an oxymoron.

The reason is one restaurateurs almost grasp.

“Alabama-born, Dallas-raised Jeremy Sutphin, chef at Le Bon Ton, attributes it to adventure and awareness. ”I’ve been here eight years and the palates are searching for something different – and people are becoming more aware.” “

He’s right about that awareness. Australia’s knowledge of America is now a lot deeper and wider – we’ve now been to America enough that we’ve ventured beyond LA and New York.

And that has happened very recently.

Why the sudden interest? In 2008, airfares to the USA were around $2300. Ouch. Today, Virgin is offering Sydney-LA return from $1229.

That results from a deliberate decision of the Australian government, to introduce competition into the market.

Here’s Labor Transport Minister Anthony Albanese talking about the “open skies” pact with the US in 2008.

“This agreement will be good for competition and it could … lower airfares.”

We’ll forgive him for not predicting the great barbecue explosion of 2012/13/14.

Of course, post-2009 also coincides with a much higher Aussie dollar. There were three good years there where you could buy a greenback for less than one Aussie dollar. Of course, those days are behind us.

So if travel predicts what we’ll be eating next, what’s the next big wave?

So if travel predicts what we’ll be eating next, what’s the next big wave?

Fairfax food doyenne Larissa Dubecki is tipping Korean food to take off. But the bibimbap futures index doesn’t look that frothy to me.

Might a renaissance of Japanese cuisine be on the cards? Perhaps. But Japan’s post-Fukushima bounce back still looks modest compared to other places Australians love to fly.

Might a renaissance of Japanese cuisine be on the cards? Perhaps. But Japan’s post-Fukushima bounce back still looks modest compared to other places Australians love to fly.

There is one extremely popular destination still terribly under-represented at the fancy end of the food business.

Indonesia’s surge is even bigger than America’s. Looks like queueing up to pay $40 for a plate of nasi goreng cannot be far away.

Marvellous! An economic history lesson from Flinders St Station

I am completely entranced by this old photo of Melbourne’s most iconic intersection.

The shot tells a story of changes in technology and economics. For starters, there are four horse-drawn carts in the photo.

While a busy Friday night in 2014 might still see a horse and carriage at this intersection, in 2014 they’d be pulling regretful tourists, not valuable cargo. The decline of the horse and rise of the car coincides with the industrialisation of the fuel-making process. In 1927, oil company Mobil was just 16 years old.

Here’s a Google Maps image of the intersection today.

The tram stops also tell a story of change, not so much in technology as values. The tram stops of the jazz age – located in the middle of the street, amid a stream of traffic – amount to little more than a bit of paint on the ground. That has changed. Tram stops now are highly protected from traffic, probably because the value society places on human life has risen along with wealth and productivity.

One familiar thing in the shot is traffic. We see cars stacked three across and two deep, getting ready to hook turn from Flinders St onto Princes Bridge in the foreground of the shot. (For non-Melbourne readers, the hook turn is a unique form of torture inflicted by this city on unwitting drivers, for the purposes of mirth.)

The street at the top of the photograph – Swanston Street – is now closed to car traffic. The externalities associated with car traffic are very clear in this intersection, as early as 1927. (I am referring not to pollution, but the way the presence of one car on the road slows down all the others.) The proliferation of cars in the last 90 years means these externalities would have developed to city-threatening proportions had the use of cars not been limited.

The crowds suggest patterns of work is much the same. But it doesn’t show the city at night, which would reveal far more differences in society, in dress codes, and the purchasing power of young people especially. Zooming in would also reveal big differences in ethnic composition, thanks to the ease of global travel.

There are no bicycles in the shot, which is a surprise to me. Standing at this intersection now, you’d struggle to frame a shot without a bike in it.

Apparently cycling was extremely popular in the 1890s. That enthusiasm has seemingly waned by the time film was exposed for this shot. Will Melbourne’s current love affair with bikes also prove transitory, or is this shot just unrepresentative?

There have been a lot of technology changes since the 1920s. One of the most dramatic is in construction. Despite being a shot of the city, this photo, repeated today, would not show any sky scrapers. This area has heritage protection. Perhaps there were height controls even then – the shadows reveal bigger buildings lurk just outside the frame.

Most of the technology changes since the 1920s are at a smaller, human scale. The contents of the pockets of the people in the shot is probably where the most dramatic changes would be evident. The one clue we have in this shot to that sort of technological change is the fact it is shot in sepia.

There are a lot of lessons in this old shot, a lot of differences. But the biggest single point is probably the similarity.

The crowds swarming across Flinders St look exactly as they do today. That suggests the patterns of life – catch a train into the city, go to work, go home – have not changed too much. And three of those four corners – the railway station, the pub and the cathedral remain the same. Only the old Princes Bridge Railway Station in the bottom right is gone, replaced with Federation Square.

The trams in the shot are cable trams – they are not powered by electric wires but pulled along by a cable that ran beneath the street. [edit: apparently cable trams were replaced by electric trams the year before this shot was taken.]

Despite the advent of electricity and computers, trams still follow these same routes.

This shows the way infrastructure and patterns of human life endure. Technology is often first used to do the same old tasks a bit differently. We don’t quickly end up in a Jetson’s future, but a sort of inverted Flintstones, where the objects are much the same and the technology behind them is different.

(Cable tram video you will find terrific if you like history, Melbourne or public transport.)

What else do you notice about this photo? Please leave a comment!

Economics of Graffiti

Sometimes I ask myself if market forces are broken. All over my suburb I get art, totally for free.

An army of workers accept nil pay, terrible hours, and poor conditions to head out and paint each night.

Not only do they work without pay, but they are forced to buy their own materials and if they get busted, the justice system is not kind.

Not only do they work without pay, but they are forced to buy their own materials and if they get busted, the justice system is not kind.

I guess the economists whose models rely on rational actors maximising their consumption never woke up to find this on their back fence:

What motivates these characters? Is it the cash??

What motivates these characters? Is it the cash??

Once upon a time, the notion would have been ridiculous. Graffiti was a way to raise your status among people who never had the chance to finish school or get the Benz. There was no money in it.

Is graffiti different today?

Piece by Putos.

The answer is both yes and no.

The graffiti economy works for guys like Cope2, who grew up in the Bronx and illegally painted subway trains for 20 years before cashing in. He sells pieces for around €3000. Banksy is the other case in point – probably the most notable street art millionaire.

Sheaprd Fairey (the HOPE guy) has also cashed in big time with his OBEY clothing line. Even Justin Bieber is dabbling in “street art.”

Then there’s things like this:

How has graffiti gone from definitely underground to potentially lucrative? The difference is in the web.

Some graffiti really caught my eye when I was growing up but it was difficult to take interest in what was going on and turn it into understanding or appreciation.

Then the internet came along. I contend that it has done for graffiti what radio did for music. Made some superstars.

The first Melbourne artist I really googled is Rone, who paints pretty girls all over the place and is kind of a gateway drug for graffiti appreciation

Rone’s instagram reveals that he has recently been in Miami for Art Basel, after a stint in London painting in Shoreditch and being hosted by a gallery to paint a huge wall in Berlin.

The guys who I first noticed up around Collingwood and Fitzroy are from the Everfresh Crew. They have an extensive internet presence and advertise services for rent. Oh yes, there’s money in them thar walls.

Collingwood’s Backwoods gallery is also in the game. They bridge “the gap between the street and the gallery wall, whilst remaining authentic to their artists’ history and vision,” by selling prints for around $100.

There’s not heaps of cash in it, but there is certainly the opportunity for travel.

Some Melbourne artists I follow on Instagram (e.g. dvate) recently took off for the Tahiti Graffiti festival (sponsors include a hotel chain, a bank and the Alliance Francaise.)

Many were already Pacific-savvy after having recently gone to the Hawaii Graffiti festival (sponsors include an airline and a clothing company.)

It seems the internet lets the artists who patrol the night control their image, and helps make money from it.

So is graffiti just another culture co-opted by capitalism?

Not yet. Melbourne’s graffiti scene is arguably dominated by two names. Jetso and Pzor. And this is where you can go down the rabbit hole and end up like me, taking a photo of a dumpster.

If you start looking for them, they are everywhere. Their work tends not to be elaborate pieces but quick bubble-letter throw-ups, tags and stickers.

They have no website, no instagram, no representation in the gallery scene (as far as I know). Their art is not visually appealling at first. The art is in the effort. It’s hard to find a part of inner Melbourne, east to west, that shows none of their finger prints. Once you start to notice, it’s hard not to admire.

For these guys, there’s no money in it. And that tells you that for them, graffiti is not work. The question I asked above about market forces being broken is irrelevant. For these guys, painting is leisure. They’re doing it for the love of it. I respect that.

Melbourne is an amazing place, and it gets even better if you can appreciate the art that’s all around you. Here’s three amazing Melbourne graffiti artists you should know.

1. Rone

2. TwoOne

3. Lush (The artist behind the pirate cat. Also dabbles in cartoons. Often nsfw (not safe for work.))

How to think clearly about skyscraper proposals.

A new 50 storey building is being planned at Melbourne’s highest point, next to a park called Flagstaff Gardens in the centre city. Continue reading How to think clearly about skyscraper proposals.