The internet economy is developing before our very eyes. Is it a gold mine? Looking only at the Silicon Valley Ferraris, you might conclude yes.

Or is it going to destroy value and jobs everywhere? Looking only at the newspaper industry you might conclude that every job that involves storing, processing and weighing information – from lawyers to bankers, doctors to teachers – is in deep trouble.

The internet reduces a lot of costs. As consumers we are comfortable with the concept of zero marginal costs. We breathe the air, look at the views, bask in the sunshine.

But as producers, as workers, we get worried. There are no jobs in the “Air Industry.”

The internet means a lot of work is about to be done at zero marginal cost. You build a system that teaches kids their time tables, you can roll it out across the English-speaking world. Teachers quake. Build a system that retrieves data from legal cases and roll it out across the jurisdiction. Lawyers will quake. Build a system that uses symptom data to develop diagnoses and hospitals will take it up while Doctors rend their garments.

But all this is a long way off.

For now, the internet is a lot simpler. The only industries that have been transformed so far are ones where data is simply displayed, not manipulated. Industries like advertising.

Google shows you ads all over the internet – in your email, when you surf the web, etc. And this transformation has reaped it a large and growing pile of money.

Until now.

Google revenues have fallen in all categories in the first quarter of 2014.

Meanwhile, costs rose and operating margins fell to 27 per cent. This was quite a surprise and the stock fell sharply in after hours trading.

Of course Google is still profitable, and Q1 2014 beat Q1 2013, but the movement in the trend provides another data point to support the second hypothesis above, that the internet-isation of our economy will not involve a lot of money.

The internet is just a distribution mechanism. Making information for distribution still takes work, at least for now. But economic theory says the cost of a good will fall to its marginal cost. The predictive power of economics is pretty impressive when you look at how many newspapers are free, how many TV stations are free, and how many movies get pirated.

Whether companies will find ways to get people to pay for information products is an open question.

But if the “zero marginal cost” feature of the internet economy proves to be decisive, investors will lose a lot of money. Evolving views on this “big question” may explain why the Nasdaq – the technology stock index – surges and falls with more volatility than other bourses.

Some investors clearly already worry about the profitability of technology companies.

But money is not everything. The world in which zero marginal cost is decisive could be a good one.

Imagine if air was made in big O2 factories, and you had to buy a subscription. Would you be better off, or worse off?

So it could be with a lot of technology. We may be better off in an economy where there are slightly fewer jobs but much more that you can consume for free.

Even if the robots don’t get up to scratch and we need people to make information products for free, will we be able to expect them to do so? Let’s look past the evidence that they will (YouTube, blogs, most short films, most bands, Open Office, a lot of apps, Wikipedia, etc.) to the theory.

The concept rests on the idea that people have a “cognitive surplus.” You can meet your basic needs (food / housing) without using up all your week. Then you have time you can spend doing things that look like work.

This cognitive surplus may come in a certain phase of life. You may be a child or a student or retired. Or you may have a cognitive surplus because you work part-time, or because you are still full of beans in the evening when you get home from your “real” job.

The you use that cognitive surplus to do things that look, to the outside observer, like “work.”

The fact that a cognitive surplus needs to be defined and explained, really shows the incredible power of one of economics simplest models: breaking your day up into Leisure and Labour.

The model is pervasive. People use it to do all sorts of calculations about how much they should pay to save an hour of leisure, etc. But it’s also kind of stupid. Commuting is neither leisure nor labor. Neither is washing your work shirts. The category of unpaid labour is invented. For washing the floors, sure. But does it include baking a cake? Digging in the garden? Building a treehouse? You can enjoy unpaid labour.

Slate economics blogger Matthew Yglesias goes on and on about the enjoyment of your job, calling job amenity value the most neglected subject in economics. Of course you can enjoy paid labour too. This is just another way in which the binary “paid labor vs unpaid leisure” model of life is defunct.

The internet could end up making the leisure/labour model look even more stupid, if people accept they won’t get paid for things that were once deemed work, and do them anyway.

They’re spending their cognitive surplus. Is it leisure or labour? Wrong question.

If the zero marginal cost economy takes hold, quality of life may even go up, because people can consume more. It’s the same sort of change that came upon society when the printing press was invented – a huge decrease in the cost of distributing information, and a lot fewer book-binding jobs for monks, which caused a fuss at the time.(And of course the printing press itself wrecked a few legacy institutions.)

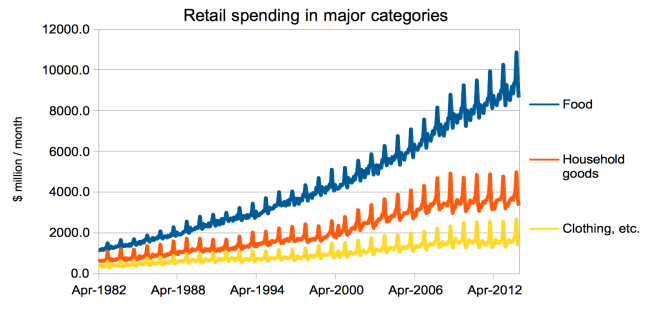

But a zero marginal cost economy won’t wreck the whole economy. There will always be plentiful jobs in things that are not zero marginal cost. Humans need food and housing and transport and always will.

If you’re worried about the rise of the internet, invest in something concrete. Like iron ore mining, or potato farming, or logistics. These industries will continue to sell things, hire people, and make money.

The idea is so clever that Google now has software that is entirely designed to trick us into doing work for them.

The idea is so clever that Google now has software that is entirely designed to trick us into doing work for them.