The election is no longer “on the horizon.” It’s close enough to smell the sausages. Everyone involved in politics is working hard, trying to get us to listen, trying to get us to believe, trying to get us to vote.

Most of what they are saying is lies. Or to be a little kinder, false predictions about what they will do in the future.

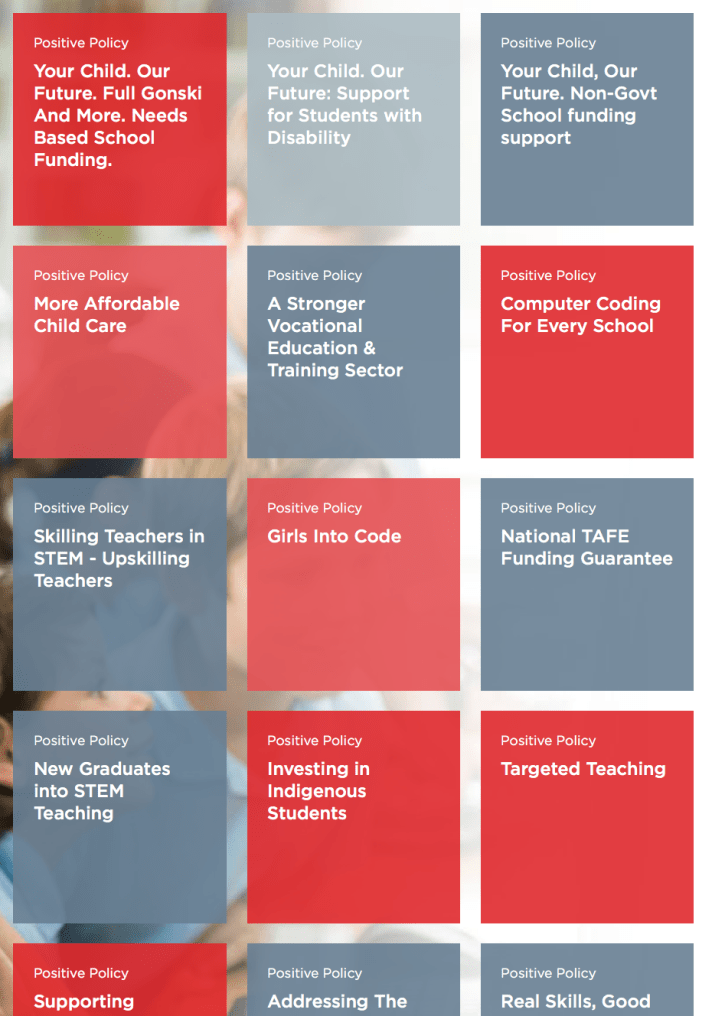

Labor has set out 100 positive policies on its website.They’re really quite interesting and I recommend having a look.

But will it do them all? No way.

Take its plan to cut capital gains tax and negative gearing. These are very bold reforms any party would struggle to get through the Senate.

And – despite recent reforms – the coming Senate is going to be a particularly mixed one.

Psephologist Anthony Green predicts eight Greens, three Nick Xenophon Teamers, either Glenn Lazarus or Pauline Hanson, Jacqui Lambie and an associated senator, plus probably one other odd-bod from Tasmania.

It’s a volatile mix that would wreak havoc on the most carefully-planned legislative agenda and laugh heartily at the very idea of a mandate.

And there is no guarantee of a mandate, for anyone. A hung parliament is quite possible, with independents and Greens set to make good runs in a range of lower-house seats. Nick Xenophon Team is a huge factor because it is competitive in some classic Coalition seats in SA. One expert tips six cross-benchers.

The odds of a hung parliament are 4:1 against and the closer the two major parties get, the better the chance a couple of independents (Yes Tony Windsor, I’m thinking about you) could have the parliament in the palm of their hands.

What all this means is that words spoken before the election – however earnestly meant – cannot all come true.

Why don’t politicians admit that?

Instead of having broken promises littering the field of battle, creating the impression “they’re all liars”, why not explicitly admit some outcomes are state-contingent?

They could make promises contingent on election outcomes:

“If we win a Senate majority we will pass all our policies. If not we will make health and education our top priorities.”

Promises contingent on Budget outcomes.

“If company tax revenue rises above $100 billion, we will fund a new hospital in Launceston.”

Or promises contingent on other promises.

“If we can get our negative gearing reform bill through, we will fund the building of submarines in South Australia.”

Politicians demur on hypotheticals for a reason – adherents of the more cynical schools of political communication will insist the complexity is too high for voters. And I’m sure the first few weeks after adopting this approach would be full of mocking.

“The Leader of the Opposition is a maybe man, a possibly politician, an if-then individual,” the PM would jeer. “He’s built an escape route into every promise!”

Perhaps most politicians would wilt immediately under such ripostes – and the bad press that would follow. Gallery journalists – whose expertise in reading the tea leaves might be slightly less valuable in such a scenario – might be unwilling to give the approach a decent chance.

But maybe, just maybe, a contrast would eventually become apparent between one side explaining their priorities and the risks and contingencies while the other side baldly claims things that can’t all come true will all come true. It just takes one politician floundering when asked, “But what will you do if you don’t control the Senate?” for that to become the favourite question of press-packs everywhere.

If so, the pressure for truth-telling would ultimately fall on the party that over-simplifies their plan. If that party won an election and then failed to keep their promises the consequences would likely be harsher, given the good example set in advance.

There would still be plenty of opportunity for broken promises. Sometimes politicians simply do the opposite of what they say they will, as Tony Abbott demonstrated after the last election.

But without the cover of all those things promised that were only really deliverable under very particular circumstances, the flat-out lies would be much easier to see.

By his second term, Obama took a hard-line position to negotiating and the Republicans were the ones that copped the blame for the government shutdown of 2013.

By his second term, Obama took a hard-line position to negotiating and the Republicans were the ones that copped the blame for the government shutdown of 2013.