I love government. But it is not a blind love. Government is not done as well as it could be. I’m very much for the idea of achieving collective goals to improve society, and very much open to reforming how we do that.

Here in Victoria we have two of the most potent and innovative public agencies: TAC and WorkSafe. The Transport Accident Commission works to reduce injuries and deaths from transport accidents. Worksafe works to reduce injuries and death at work.

They do a lot of good preventative work. Both have been very effective.

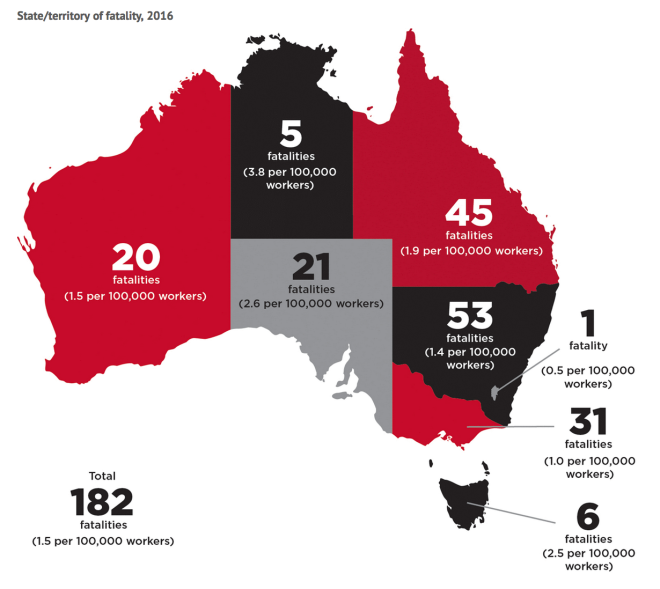

Victoria has the second lowest workplace accident rate in Australia, measured by fatalities (after the ACT) and by workcover claims (after the NT), as these next two figures show.

1.

2.

2.

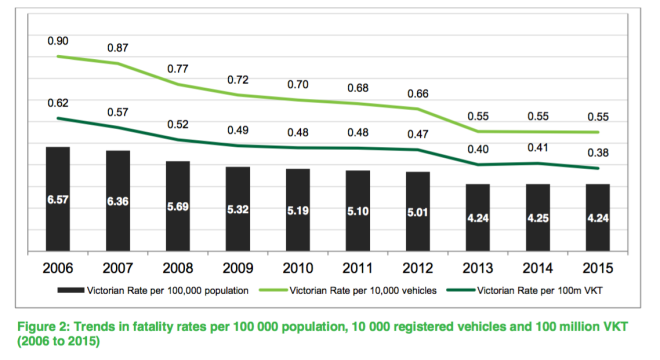

Victoria also has some of the best road safety performance in Australia. It has improved substantially over the last decade, as the next chart shows. (Of course, improvements in safety also come from improvements in cars themselves, but via programs like How Safe Is Your Car? the TAC encourages Victorians to buy safer cars, accelerating those positive changes.)

What makes Worksafe and the TAC effective?

- Reason one is their independence. (The 2014-15 blip in Worksafe performance that you see in the above graph may be related to the state government meddling with its operations at that time. Independence matters.) They are statutory agencies free from direct ministerial control, giving them the ability to take extra risks.

The innovations that are most visible to the public are their communications – Worksafe sponsors a football team while the TAC pioneered using TV advertisements to change culture and reduce the road toll. This kind of communications strategy is rarer in government departments, where ministers face tough questions over spending. - The second, related reason is that these are not just policy agencies but insurers. Worksafe takes premiums from employers, and TAC from car registrations. They pay out when a worker is injured, or when a person is injured in a vehicle accident. This gives them not only a funding source independent of annual budget rounds, but also a clear financial incentive. (nb. Worksafe is also the workplace safety regulator and inspector, giving it further powers. TAC is not.)

These are both world-leading organisations which have had powerful positive effects on society, and organisations whose successes I have admired. So I was excited to see, earlier this year, the head of the Productivity Commission throw up a powerpoint slide with a dot point that argued we should “Address disease prevention as directly as we address workplace accidents.”

I was immediately captivated by the idea of using the Worksafe model to try to fight disease. The upside looks to be huge. Australia’s preventative spending on health is fairly terrible, as is well-documented, and was again confirmed in a paper by two Public Health academics in July this year.

“Treating chronic disease costs the Australian community an estimated $27 billion annually, accounting for more than a third of our national health budget.

“Yet Australia currently spends just over $2 billion on preventive health each year, or around $89 per person. At just 1.34 per cent of Australian healthcare expenditure, the amount is considerably less than OECD countries Canada, New Zealand and the United Kingdom, with Australia ranked 16th out of 31 OECD countries by per capita expenditure.”

Could we fix the preventative health spending deficit by setting up organisations akin to Worksafe and the TAC? Might it have the exact combination of novelty, innovation and actual prospects for success that could make politicians and public servants agree on it?

At a high level the opportunity seems to be there (for preventable diseases but not, so far as I can see, for non-preventable ones like MS). Does it persist when you dive down into the details?

THE DEVIL INSIDE

Imagine you were setting up a statutory insurer to fight against adult-onset diabetes. The insurer would collect premiums and pay for treatment after a person was diagnosed.

The big question is where the premiums would be levied. There is a key difference between this scenario and the workplace safety situation. Employers opt in to insuring employees when they hire them. Likewise, road users opt in to the TAC scheme when they register a vehicle.

The sort of population-wide coverage required by a diabetes insurance scheme means the beneficiaries could not be expected to cover their own premiums. (i.e. not without undermining the public nature of the health system! This fact may motivate some skepticism towards this idea from people who fear it is a Trojan horse for dismantling public healthcare. I don’t think it is.)

IT ALL COMES BACK TO CANBERRA

The only plausible premium-payer would be the federal government. That raises the question: How different, ultimately, would this be from Medicare? If the government is paying premiums into a public insurer and taking out the payouts to cover treatment costs, isn’t this just replicating an existing system?

The answer is it might be a replication. But if there is something in the culture, funding or control systems of the Health Department that makes it less than optimally effective, then there is a chance of improving outcomes by making a new organisational structure.

Following the Worksafe and TAC models, a good insurer would be focused on a single disease or group of diseases that we have at least some ideas how to prevent (lung cancers, diabetes, heart diseases). It would work on culture change and system changes to try to find the most cost-effective ways of reducing the incidence of that disease. (As an example of systemic changes, the organisation paying the premium might be more inclined to levy a sugar tax if it knew that would reduce its premiums for diabetes insurance). If it had success, the premium it would have to charge to the government for coverage would fall.

NDIS-ESQUE?

Any such systems would be different from the NDIS. The NDIS is far more about organising and coordinating the care for people who have disabilities. It is premised on helping people after the fact and is a vital service.

It does not seem, so far as my reading has shown, to have a focus on identifying avoidable disabilities and investing to avoid them. ( I am sure there are exceptions down in the details but at a high level NDIS is more about service-delivery than prevention.)

ISSUES

I’ve painted a picture above that I find promising, but I’m not going to expire in the proverbial drainage channel for this idea. I can see its weaknesses.

For starters, this looks like a case of bower-bird problem solving. You spot a shiny thing (TAC, Worksafe) and take it back to your nest. Then you’re seeking out a good way to use it. That is different to taking a first-principles approach to figuring out how best to optimise preventative spending. There may be better ways. And it could be that the azure sheen of TAC and Worksafe blinds one to the inherent unsuitability of the model in other environments.

Secondly, I may have mis-identified the effectiveness of those two organisations. I know their existence correlates with big improvements in the outcomes they’re targeting, and I know they are well-regarded but I can’t show causation. Other jurisdictions have similar organisations that are not as effective.

Third, the advantages might all fly out the window when you have the federal government paying the premiums rather than other customers. That’s a powerful customer and it might be hard to fight for justified premium hikes in tough fiscal situations, in which case the independence of the agencies becomes blurry.

Having said all that, I’d love to see a superlong .pdf getting into the guts of this idea and figuring out whether there is promise in it. If you work for a thinktank or a department and you’ve already written such a thing, please let me know!

Anyone else, please leave a comment sharing any insights or aspects you think are relevant!

Great to see another post Jason, and a surprise reward pupper in there too!

It’s certainly an interesting concept, and one that would likely need to be done on a federal level rather than the state examples of Worksafe and TAC. Whether it’s the right model, I don’t know. But what I do know is that I doubt there will be any appetite for significant changes from either major party to take a leap of faith and actually be ‘innovative’ in addressing issues (not just in this area, but any). It’s certainly interesting food for thought though.

(Side note: I think you left a sentence on Worksafe staff bonuses in draft mode, unfinished)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks John. I think the puppers should become a permanent feature. They’re going to supercharge those all-important engagement metrics and keep upper management happy.

As for the boring parts of the post, I agree it would be best if it were federal but I guess there’s nothing stopping the states from giving it a crack. Health is supposedly partly a state responsibility after all!

LikeLike

Good interesting stuff Can u find a publisher for dough…. What abt adani mine swowers on abc now?

Sent from my Samsung device

LikeLiked by 1 person

The most effective preventative health project in my opinion would be a compulsory subject in every school from year 5 to year 12 on healthy living. It would have a large component on diet and exercise and relate that to physical and mental development, It would show a relationship between sporting prowess and diet and exercise; and negatively between very poor diet (with examples) and lack of success. Similarly there would be a close relation between diet and exercise and intellectual success. Using the figures you quote in the article we could expect the Government to save many billions of dollars annually which could be spent on greatly improving the quality of public education in the schools, TAFE and universities.

LikeLike

The implicit assumption is that people will live they way they’re taught in school, and not the way they’re taught by literally everything else in society…

LikeLike