In the SMH, Jess Irvine has written a post accusing the rich of not paying enough tax. Strong piece. Very clickable, quite memorable, and in places, very reasonable:

“It is right to think that rich people should pay more tax than the poor. Happiness studies show an extra dollar means a lot more to a poor person than a wealthy person. So, we maximise society’s wellbeing when we raise taxes from the rich, rather than the poor.”

In the AFR, an equally strong reply:

This was written by the gossip columnist though, which suggests The Fin is passing up the opportunity to really take the bait.

This was written by the gossip columnist though, which suggests The Fin is passing up the opportunity to really take the bait.

All this has me thinking. Do the rich really pay enough tax?

Instinct says “No!”

There is, however, a bit of cognitive dissonance the average policy wonk faces in answering such a question.

Let’s face it. Most of us consider that question by imagining those richer than us paying more. Few readers interpret it as “should I pay more tax?” even though plenty of you find yourselves in a household making over $100,000 a year.

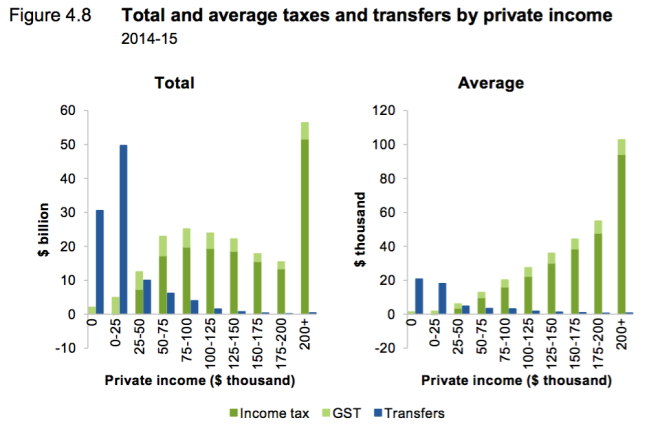

Secondly, the average policy wonk already knows the facts. (The graphs that follow come from a terrific Productivity Commission report that is just a few months old.)

Those on higher incomes do pay the most tax in Australia. The few families making $175,000+ a year contribute more total tax than the (far greater) numbers of households making under $100k.

The tax burden is squarely aimed at the top of the income distribution curve.

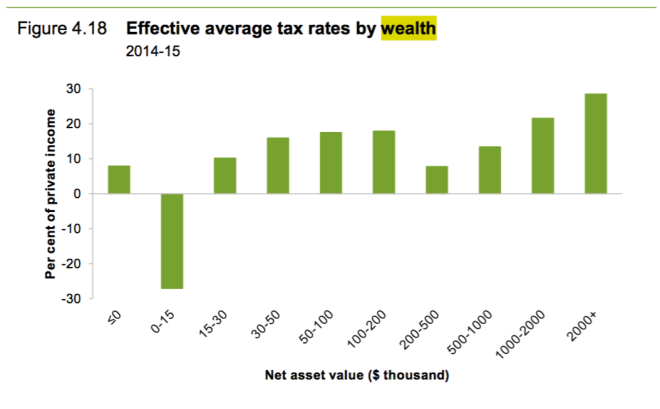

The tax burden is squarely aimed at the top of the income distribution curve. When you look by assets things get a bit more complicated, but the overall trend is still richer people tend to pay more.

When you look by assets things get a bit more complicated, but the overall trend is still richer people tend to pay more.

n.b. for whatever reason the data above is by group not decile, and the groups aren’t evenly sized. Sorry. Here’s the distribution of actual households across those groups:

n.b. for whatever reason the data above is by group not decile, and the groups aren’t evenly sized. Sorry. Here’s the distribution of actual households across those groups:

One technique Jess Irvine uses to support her call for more tax on the rich is raising the spectre of widespread income tax rorting.

One technique Jess Irvine uses to support her call for more tax on the rich is raising the spectre of widespread income tax rorting.

I wrote about rorting in Crikey last year after we learned 55 people who earned over a million dollars paid no tax in 2012-13. That fact went viral. But it represents just 0.6 per cent of millionaires.

Most income millionaires seem to pay a lot in tax – 93 per cent of them are in a group with an average tax rate of 42 per cent. Another 6 per cent pay an average rate of 35 per cent.

I reckon tax evasion is far more common in corporate tax than income tax. But Irvine’s article says we can’t do anything about that.

She goes on to argue we should institute a land tax. It’s a good conclusion to what has been a fairly odd argument. I support a land tax. I’ve been pleased recently to see it getting a fair bit of attention.

But it doesn’t really follow from her argument.

It seems to me the rich already pay a lot of tax, are fairly honest about it, and don’t actually complain that much. Is that the end of the argument?

I say no.

This “do the rich pay enough tax?” question is just a proxy – an emotive, perhaps even fun-to-think-about proxy – for a question about whether our society is fair.

So, is Australia fair?

That’s a better question, because it allows that bubbling pot of cognitive dissonance to simmer down for a moment.

The answer is probably a qualified yes. It could be fairer still, if we focus on eliminating disadvantage.

We can hold onto the fact the rich pay most tax, and permit the idea society could still be fairer.

There are many ways to eliminate disadvantage, and make society fairer. Minimum wages and strong public health systems are a big part of it.

When we look at America, we see what can happen without them. That is an economy much less fair than the one we experience.

Transfers are another major way to make a nation fairer. A basic income, or minimum income policy would go a long way to making Australia fairer. But I don’t see arguments for hiking taxes on the rich helping create the sort of consensus necessary for that change.

Among the many charms of minimum wages, public health and transfers is they don’t discriminate. Everyone has access to them. It’s far harder for a Tory gossip columnist to mock the idea of Medicare than the idea of soaking the rich.

Among the many charms of minimum wages, public health and transfers is they don’t discriminate. Everyone has access to them. It’s far harder for a Tory gossip columnist to mock the idea of Medicare than the idea of soaking the rich.

So thinking about areas of disadvantage that are important to eliminate seems to be a better way of looking at fairness in the Australian context. If higher taxes are required for such policies to be afforded, precedent suggests they will fall on those with capacity to pay.

Meanwhile thinking about ways to raise the same amount of tax more efficiently is probably the best argument for land tax.

For these reasons, I’d suggest dialing back instinctively appealing arguments the rich should pay more tax, in favour of more targeted arguments about avoiding corporate tax fraud or eliminating disadvantage.

Thomas, quite a good take on Jess Irvine’s piece, but I think you too miss some crucial points, including on your preference for higher land taxes, which I too support, but only lukewarmly as a fall back. The argument about inheritance taxes is couched in terms of their “adverse” impact on the creators of the wealth – “the rich.” But an inheritance tax – or, as I prefer, an Inter-Generational Transfer Tax, does not fall on the creators of the wealth, but on their heirs and benefactees who have done nothing to earn the wealth. Can anyone justify why heirs and benefactees are somehow entitled to receive wealth they have not earned, and pay no tax on their capital gain? Increases in land taxes, or consumption taxes, or income taxes take money out of the pocket of the person who earned it. Inter-Generational Transfer Taxes do not.

LikeLike

Inheritance taxes look abominable or obvious depending on whose perspective you take.

Providing for your offspring is a pretty fundamental desire for people. The government getting in the middle of that is understandably annoying to the people who made that money (and paid tax on it already, once.)

From the perspective of the person who inherits it is just a waterfall of unearned free money and taxing it is probably fair.

You take the latter view. Which is fair enough, I’m not sure how best to choose.

All this said, i don’t read Irvine’s piece as an argument for inheritance taxes. She is just using post-mortem payment as a solution to the problem of levying land taxes on the cash-poor, asset rich.

LikeLike

I’m in the bottom half of the top quintile for wealth. As a beneficiary over quite a few years of negative gearing, the capital gains tax discount, and superannuation tax concessions I cannot for the life of me justify why my concessionally taxed retirement savings, and my principal place of residence should be able to pass to my children without any additional tax. I don’t know how long I will live. I would rather the certainty of income and my retirement savings until I and my wife are gone. My recommendation – see my submission on the Treasury Bettertax website – is for a modest (GST rate), universal and mildly progressive tax on all inter-generational transfers. On my numbers a very easy $13bn in 2015-16, though if Ben O is right my number should be a lot higher.

LikeLike

Joe – sounds like the problem is with negative gearing, CGT and super concessions, not the lack of a death tax. Also – incredibly hard to enforce with the creation of family trusts and significant gifting in people’s latter years. Would create mountains of red-tape.

LikeLike

G, I partly agree, but the disagreements are important. Have a look at my submission on the Treasury Bettertax website. What I am proposing is not an inheritance tax per se, but a tax on all inter-generational transfers of significant assets for below market prices. Not a difficult concept, and not practically difficult given that cash is cash, shares have a market price, and cars and real estate have good-ish price guides and, when it comes to probate, all assets (and liabilities) are valued and sworn before a court. And yes, I would apply the tax to the creation of a family trust, as I would to charitable donations. Not popular, obviously, but ask yourself: is that fairer for society at large and financially better for you and your partner as individuals that hitting you up with increased land taxes or GST through life? A rational analysis tells me it is, for the overwhelming majority.

LikeLiked by 1 person

https://pirateparty.org.au/wiki/Policies/Tax_and_Welfare

LikeLike

I would encourage you all to stop and think not about tax but about the government. At the beginning of federation in 1901 the federal and state governments combined only consumed 5% of GDP. Today they consume 35% of GDP. They have enough of our productive capacity. The problem is in the government not with us. Thinking that we need to give them more money is not thinking at all. As Einstein said “you cannot solve current problems with current thinking. Current thinking is the cause of current problems”.

LikeLike

“At the beginning of federation in 1901 the federal and state governments combined only consumed 5% of GDP.”

In 1901 there were no pensions or public healthcare. Universities were full fee. Queensland didn’t even have free high schools. In fact public utilities and services were pretty much non-existent.

LikeLike

It simply untrue that the US has low taxes. Their overall tax rate (26-27% of GDP) is virtually identical to Australia.

http://www.treasury.gov.au/Policy-Topics/Taxation/Pocket-Guide-to-the-Australian-Tax-System/Pocket-Guide-to-the-Australian-Tax-System/Part-1

US Federal income tax is low but there are many state and local taxes. Property taxes are high and they have death duties.

LikeLike