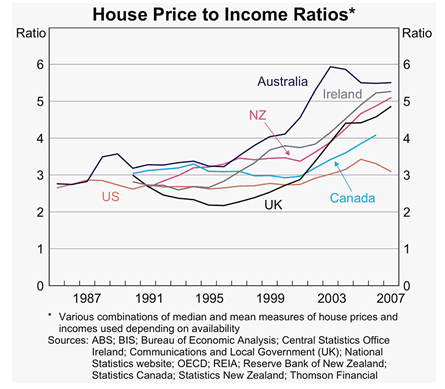

No. Despite the fevered warnings of some commentators, this RBA graph does not portend a housing crash:

People can deal with their basic needs using a smaller and smaller proportion of their income. This leaves more and more to spend on your mortage.

Here’s a little model to demonstrate what I mean: Let’s pick a point in the past (1995) where someone is making an amount of money (50 grand). Imagine that person spends $17,949 on consumer goods and services and the rest goes on their mortgage.

The ABS tells me that wage inflation means the same wage is now $95,828. CPI means that the same basket of consumer goods now costs $26,414. Doing the same job, buying the same stuff and obeying the tax laws, a person now has 2.5 times as much to spend on housing!

The big assumption here is that housing budgets expand to take up the left over money. This is not perfectly realistic. Consumption expenditure will also increase. But the people do scrimp to pay their mortgage. Because they expect growth, they want to make this investment as big as they possibly can.

We can see support for the assumption, here:

Housing expenditure has grown fastest of all categories of household expenditure. People rush to expand their housing budget before their other consumption

There may be other factors distending the old ratio of household income to housing price.

Multiple income earners. What proportion of housebuyers are now a two income team? How has this changed?

People also may be willing to take on bigger longer mortgages now. Maybe due to

- Macroeconomic stability – recessions less often and less deep

- More predictable and stable interest rates (the RBA controlling monetary policy)

- Longer lives

- More flexible labour markets mean a more stable income stream.

I want to conclude, like an economist, by hedging my bets. I’m not saying ‘housing markets won’t crash’. I’m just saying that a changed price to income ratio doesn’t make it axiomatic that they will.

I also think that a lot of this discussion obsesses on averages and medians. It’s not that useful in this context.

The ABS reports today that median tshirt sizes have increased to L. Skinny people are petitioning the government to do something, anything, so they are not left naked in the rain.

“Adequate clothing is a basic human right” said one protestor today, baring a remarkably slender torso.

Measures of central tendency do not help us determine whether everyone can find a match that’s right for them.

LikeLike

Some say that Australia’s very high house price is a consequence of the capital gains tax free status of the family home. Thus people put the majority of their money into something that will be tax free.

LikeLike

“More flexible labour markets mean a more stable income stream.” I found this statement a bit curious. My career has been mostly in jobs that have been on contracts with no guarantees of renewal. Many jobs that would have been on more or less “tenure” or ongoing basis in the past are now on revolving one year contracts or “long” term contracts of three to five years. Maybe it’s just me, but I grew up with knowledge of 17% interest rates in the 80’s boom, and finished high school in the recession in the nineties and pretty much had to leave the country to get a job in the area I studied in uni as did a lot of my friends. In the early nineties you were doing well if you could get a waiting job after your graduation. I’m paying off my mortgage on a fast track and expect things to get worse not better.

Have you watched Elizabeth Warren’s lecture “The Coming Collapse of the Middle Class” – sure it’s about the US but it still has many similarities with Australia.

LikeLike

I’ll concede that point. I guess I was imagining that if your factory went broke, back in the day, you were done for. These days it’s more normal to find a second or third career. But I suppose that flexibility cuts both ways, and that might make it harder to take on a big mortgage.

LikeLike

Christopher Joye from Rismark seems to be able to account for the rise in prices fairly well, but I think Robert Shiller’s emphasis on the stories people tell in explaining markets also has a strong reinforcing effect. Coming back to Australia in 2005 I was surprised at the sudden popularity of real estate. Everybody was talking about it. After 15 years of property rises and general strong economic performance it would be surprising if people wouldn’t be prepared to overspending on property.

LikeLike

Yeah, i’m pretty much screwed.

LikeLike

Talking about house-price ‘inflation’ is difficult. It’s easy to compare the prices, but hard to compare the value of houses over time.

These days, new and renovated houses are bigger, better designed and full of features.

But even existing, unchanged houses offer a totally different set of features to a buyer.

The neighbourhood a house is in may have undergone change. Could be that the local shops have all closed down, and the traffic between there and likely destinations is much worse. In which case the same house offers much worse value.

Or it could be that the neighbourhood has gentrified, a bunch of quality services are now on the doorstep, proximity to the train station is now considered a plus, and the address is now perceived as prestigious.

In this latter case, the house may now offer a much better value proposition to whoever buys it.

LikeLike

The main reason price-income ratio should not be stable is interest rates. Even if the same portion of household income is spend on housing (which it roughly is), then a halving of interest rates will double prices even though the cost of buying is fixed. When you adjust for this you see prices are pretty much reflective of asset market dynamics

Also, relative to recent history, homes are reasonably affordable.

This post will be of interest

http://ckmurray.blogspot.com.au/2013/09/house-price-signal-flashes-green.html

LikeLike

No, house prices shouldn’t be a consistent multiple of income. At least, not wages but closer to household income.

In the 1950’s, most homes were single income homes. Nowadays, most homes would be 1.5 – 2 income homes. This is one reason how households can afford bigger mortgages. In 1950, an average wage might have been 1,500 quid when house prices might have been 2,500 quid (grandfather’s experience in Moorabbin, Vic.) So, average house prices less than 2 times average wage.

Nowadays, average young family household income might be $100-120,000 and average new home might be $350-400,000 (Adelaide, 2017 approx.) Middle income earner might earn $150k per HH and average home might be $450-500k. So here, house prices are about 3 times HH income (rough estimates of values by a mortgage broker in Adelaide, SA (me).)

I think your argument that portion of income available to go toward housing is correct. I guess the increase in technology has allowed greater production and consumption of G&S without a commensurate increase in cost, allowing more income available for housing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Damn, Adelaide is a bargain!

LikeLike

An interesting phenomena is that land has historically increased in value at approx. 7% pa whereas incomes have increased at perhaps 4% since mid 1970’s. This growth discrepancy means that the cost of financing a home must consume more of our incomes.

This cost of housing increase necessitates greater household income. It coincides with social pressures and liberties for more women to go to work.

So a question might be, “Is the great housing price increase demand driven by greater household income?”

Or is it supply driven, forcing women to go to work to keep up with the Joneses?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve had a thesis since the mid 90s (when interest rates were pretty high), that the overall trend of interest rates will be forever down. My reasoning was (1) Japan is the canary in the coal mine. (2) Governments and central banks will always juice the economy with lower rates to avoid recessions, but they’ll never raise them enough to cause pain. Rates are not really market driven, they are driven politically, and politically its easier to move down than up. (3) The economy adapts to low rates by taking out massive loans. To then raise rates would crush the economy. Thus the low rate regime gets baked in long term.

All of my predictions have come to pass with rates getting to zero in many jurisdictions, , and even notionally negative in some countries. I don’t think anybody knows what comes next. If we look to Japan again, rates go to zero and stay at zero, and then debt just keeps growing forever. But intuition says this must somehow end.

LikeLiked by 1 person